“Prevention is better than cure.” That is highly applicable to the invention of vaccinations. Thanks to immunization, we can control diseases such as smallpox, polio and measles. Across the globe, we are currently hoping that a vaccine against the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 will be developed soon.

Smallpox

Around the 15th century, the Chinese realized that people who survived smallpox usually did not get this seriously infectious disease a second time. To prevent their children from getting smallpox, they started experimenting: they administered scabs from infected people to children. These children had milder symptoms.

Vaccine “of the cow”

The British doctor Edward Jenner used this Chinese wisdom in Europe. In 1796 he treated a milkmaid who had blisters on her hands caused by cowpox. Jenner started experimenting by infecting his gardener’s 8-year-old son with the pus from the milkmaid’s blisters. And what happened? The boy caught a mild version of cowpox from which he recovered well. When Jenner repeated the experiment two months later, but then with smallpox that is dangerous to humans, the boy stayed completely healthy. Jenner’s conclusion was that the boy was fully protected against smallpox. The word “vaccine” comes from the Latin vaccinus, which means “of the cow.”

Accidental cholera vaccine

In the 19th century the famous French physician Louis Pasteur discovered that a living micro-organism could be the cause of many diseases. He experimented with bacteria that caused the deadly cholera in poultry. When he injected those same chickens with a fresh culture of the bacteria some time later, to Pasteur’s surprise, the chickens did not get ill.

Polio epidemic claimed many victims

In the mid-20th century, a severe polio epidemic in America claimed over 57,000 victims. President Franklin D. Roosevelt is suspected to have had the disease. The American virologist Jonas Salk successfully developed a vaccine against polio in 1955.

Uncrowned vaccine king

Another significant invention followed a few years later. The American physician Maurice Hilleman developed no fewer than 40 vaccines. That made him the uncrowned king of the vaccines. One of the vaccines he developed halted an outbreak of the Asian Flu in the United States in 1957. He followed with a vaccine against the mumps in 1963, one against measles in 1968 and one for rubella in 1969. In 1971, he combined them in one vaccine (MMR), which has gone on to save millions of lives worldwide.

Expensive business

Salk didn’t have a patent for the polio vaccine. That is almost inconceivable nowadays. The costs to develop a vaccine have increased ten-fold in the past 20 years. We are talking about investments of millions to several billion euros. That is why medicines almost never come to market without being protected by at least one patent. It is therefore not surprising that work never stops to patent new vaccines, also concerning the coronaviruses. This can be demonstrated with a so-called patent landscape.

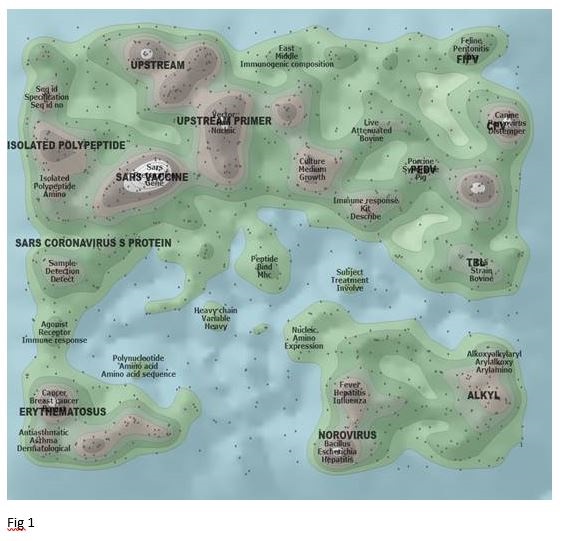

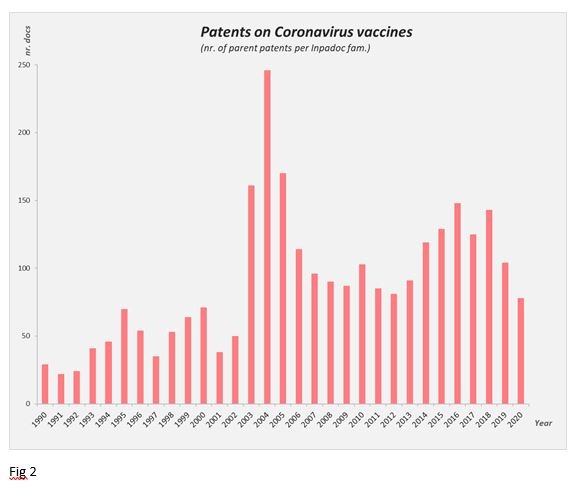

Figure 1 shows the patenting activities in particular fields using a chart with peak heights. It shows that there have been major investments in patenting SARS-related vaccines in recent years. The timeline in figure 2 clearly shows the peak in published patent applications after the SARS outbreak in 2002.